Sullivan Stapleton and Alex Russell in Cut Snake

How did you get to where you are today, where two television series Devil’s Playground and The Codeare currently airing, and your feature Cut Snake premiering at TIFF?

It seems like a crazy combination this particular year. Some of those projects, Cut Snake for instance has taken seven or eight years and Devil’s Playground was much faster than that, it was about three years, The Code about four years but they all seemed to go to the same board meeting and be filming at the same time, so it was incredibly exciting to have that. For friends it seems like everywhere you look it’s me right now but next year’s gonna be a different case. But I’ve been writing for about ten years. I had other careers before that and sort of got an office job on a TV show and just really found that I was quite good at doing it. With those TV shows the turnover of staff is high and I had that great experience of someone pulling out. That was a show called Breakers, where someone pulled out and I was given the chance to write and discovering that’s what I was good at.

In terms of starting out, how do you think the highly serialised TV format influenced your style of writing? Has it been a process thing where you’ve been able to turn things around quickly?

I think that process stuff is really important. You know what deadlines are about, you know how to manage your own time. Within that though, there are still many of my colleagues who leave things to the last minute and then doing an amazing all nighters and nail it. I’m not like that. I have to treat it like a job, which sounds pretty dull, but you get used to it. Also there’s a particular visual language that no one teaches you, even at university you don’t learn that, television as compared to film. The great thing about working on those shows was you got to see what you write shot that week and then take pleasure when you get it right, but mostly learn from it. I really liked it and don’t have any judgement on it. It’s a certain kind of thing but you write your bum off for two or three years when you’re young and it was a terrific experience for me. All of my peers from those days are now are working on other programs as well.

So did that have an impact on the sort of stories you tell? I’ve heard it referred to that drama is about progressing the story, whereas you’re successful in a soap if you can spin the wheels

Gregg Haddrick from Screentime was my first boss and he said “Forget about ends, we’re all about beginnings and middles; beginnings, middles” you have to keep going back to the beginning and middle. So I think that if you’re really curious about writing, and you have ambition, then you know there are certain kinds of stories you won’t be able to tell within that half hour format. But as far as work habits and learning what it takes to write something to be filmed it’s really good and one of the only paths you can take as a writer if you’re not a writer/director and making shorts.

In terms of approaching scenes and how characters are getting in and out of them, do you have any go-to habits? With Cut Snake there’s a real effort to bring an energy to it as people enter and exit scenes. Is there a workflow you approach with that in mind?

When I wrote my first episode of Love My Way I remember John Edwards saying “You always start scenes the same way”. Everything was in a hurry, and you had to catch up, but John’s point was if every scene is like that then there is no pace, there is no hurry. You have to vary the kinds of scenes you write. I suppose what I’m much better at now is trying to think the story through emotionally with the character. Finding the times where the character will need to be still and times when the character needs to be in the middle of an argument. There’s always those great notes of “coming in late and leaving early”, but I also think there are too many rules. Try it out and you’ll know whether it works or not, but overall you have to vary your scenes Some scenes have lots of people in them, some have few. You’re trying to give a texture to the reader’s experience I think. You’re writing for producers to read and directors to get excited about. It’s not a film yet.

In recent years, we’ve seen you move into producing as well, has that been a tactic to keep more control on the work or to get a better understanding of the process overall? Or is something else behind that?

It’s probably a couple of answers. If there is a downside to working on serial TV back when I did, and I think television’s changed a bit since then, it was that the different aspects of filmmaking were quite separated, even to the extent that you were in a different building. The writers building was in one place and they would film in another part. So when you were a writer who was meant to be on set, you’d get a call and you’d have to physically go quite a way to get to set, which meant there was a suspicion between the different departments. There was a chip on your shoulder from the writers, that the actors were going to stuff things up or the directors were going to take your script from you. That’s crazy! We’re all making the same thing, but there was a tradition in Australia as well where producers, for whatever reason, would exclude writers from the final parts of the process. There are still shows, I won’t name them, where you send a script away and they send a message and tell you that your episode is on this Friday, which would be the first time you’ve seen the episode. You don’t have that in the United States, where writers are on staff, and writers have producing responsibilities because the writer is viewed as someone who can contribute. On Devil’s Playground Matchbox, for the first time, engaged me as what they call a showrunner, which is slightly different from what a showrunner does in the states. I wasn’t the head banana, but I was involved in the whole process. I was on set and involved in all the edits and post. It was incredibly useful and I’ll find it hard to go back to the other way again. Not because I was a control freak, but just when you are emotionally and artistically invested in a project, you are a very good person for people to consult regarding what was intended and certain decisions that needed to be made. Unless you’re someone like Matchbox who would pay to keep a writer on when not writing, you finish your script and that’s that. You go onto another project, which is quite frustrating.

Devil's Playground

Do you think that’s becoming the norm? With their success from The Slap adopting the showrunner model, along with shorter run series. Do you think other companies will adopt Matchbox’s model?

It’s still a new concept in Australia so some people are more or less interested. Everyone pays lip service to the idea but it is about giving a writer a voice and letting them in the room and for many people the writer hasn’t been in the room. I’ve just been to Toronto, and it was so great that they invited me to be there because writers aren’t present by and large, unless you’re a writer/director, and you realise that the press and especially the audience have lots of questions about the story and intentions behind the story. A director will know those, but a writer can provide an interesting angle. I found a lot of questions were coming to me and in most cases the way the film industry works, the writer’s not really present. Now it’s becoming a question of the writers being more assertive about asking to be part of it, or maybe it’s just a recognition that we have something to contribute and we’re not sitting there thinking “you stuffed up my story”.

It feels like it’s along the lines of give a director 120 blank pages and tell them to film this, it’s pretty hard to do.

You’re a writer/director so I can really understand, not being a director, I was really suspicious of writer/directors until I realised, if I did have the chops to make it, I would want to make it too. A director really transforms it into their film.

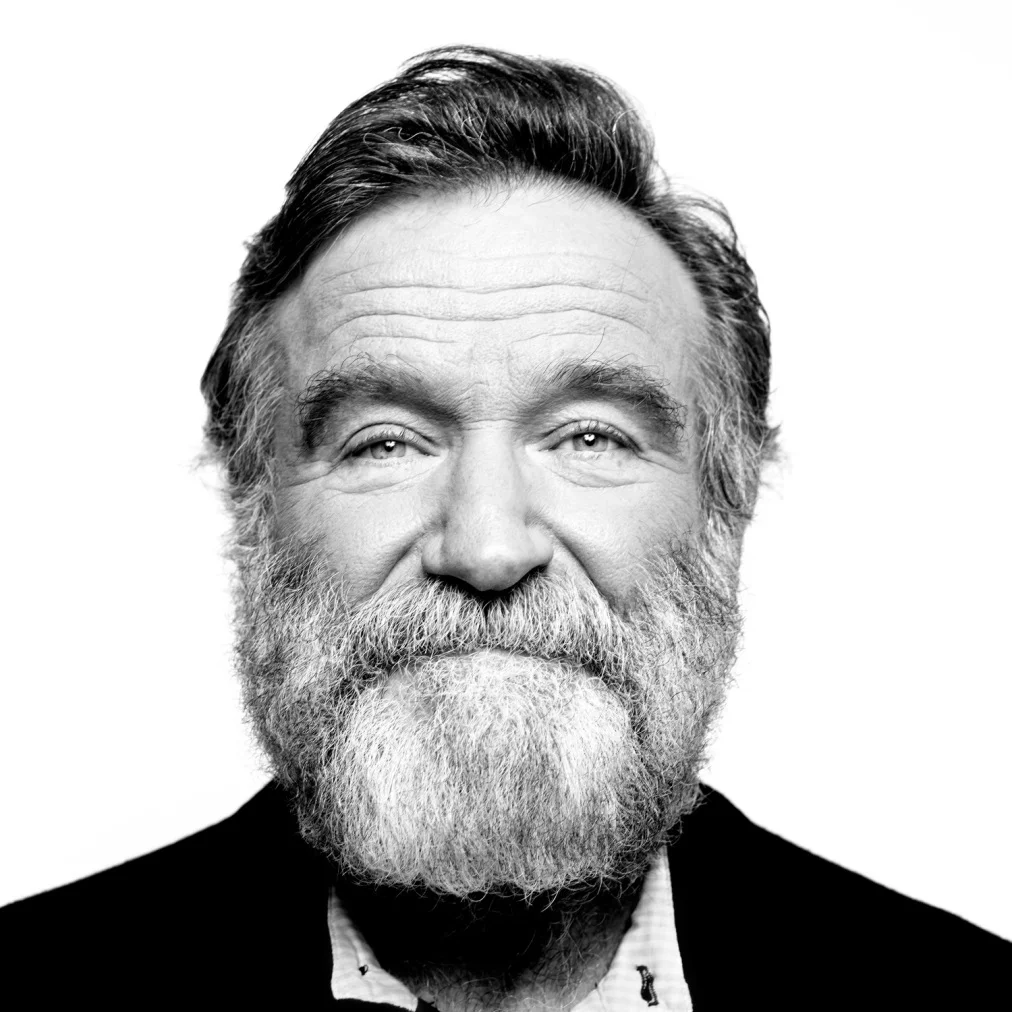

Blake Ayshford photo by Fahim Ahad

That brings me onto the directing process and I’m more familiar with your recent work. With Cut Snake being your first theatrical feature, yet having also written Rachel Ward’s telemovie An Accidental Soldier, how did those projects differ for their formats?

In those cases, it was partly a pragmatic decision. I might sound silly, but coming from a TV background, I love having an audience see what we make, and so we knew that we’d have a million people see the telemovie, but we’d be lucky if a million people see a feature film. It was an important story at a time when politically, there were a lot of people talking about the first world war, and we wanted to be part of that conversation. It seemed that the producers could make the money work in a way that a feature wouldn’t have. I didn’t really rewrite it, except for the ABC, they have a commissioning process, where they offer notes, so I was getting their feedback rather than from a distributor or Screen Australia. But as far as Rachel’s shooting style and getting Germain McMicking to film, we didn't really change anything that way from film to TV. It was also quite an intimate story that I felt could work on a television screen.

In exploring a bit more of that ABC angle, what were their notes, how were they approaching story and trying to guide it?

Because it’s about a war deserter, there was initially some worry that the ABC was not just a broadcaster, but it lends its aura to any work. They made us aware that “you do know people will think this is the ABCs position on the war” and so, I thought it was very brave of them. In hindsight, some people were interested in that element, and a lot wrote supportively towards us but they were excited about it. It was a crazy experience, I wrote a script on spec, the producers buy it and the ABC says yes all within a few months. And WA is keen to make something and this is what they want. So from the first meeting through to filming was less than 12 months. It was incredible. I mean that because TV shows often take longer than that and feature films sometimes take many years. I’ve worked with Rachel Ward several times, and recently I’ve worked with a lot of writer/directors and all three are incredibly sensitive to keeping the writer engaged, but all three are pretty rigorous in ensuring the script is what they want to film and answers all the questions they have. So Rachel was a draw as well. She’s made a feature and a few shorts, but she was still approaching this as a learning thing for her.

Moving onto Cut Snake then, for Tony Ayres, coming off The Slap this was a big project for him. How did he reach the conclusion that this was what he wanted to direct?

I knew Tony from his first film Walking on Water and Cut Snake won an unproduced screenplay competition and Tony was the judge, so we went down to the Adelaide Film Festival and had a rehearsed reading which he directed, and at that stage he expressed an interest in it but we couldn’t make it work then. I was incredibly new to the industry and didn’t know what it was all about, but I gave the script to him a year or two later. It was quite different to what it is now, it had different time periods, I was trying to do a few things at once, but he saw through to what he believed was the most interesting, original part of the story, and said “if you can write that, that’s what I want to make”. I’ve been working with him for eight years or so and we’ve become friends through it and I respond to his instincts. By the end of filming, you didn’t know what he’d suggested or what I’d suggested, it’d all mixed together.

Regarding actors, with someone like Sullivan Stapleton who’s at the top of his game and becoming a massive star...

Yeah, I can’t wait for you to see the film, his performance is amazing.

And even Alex Russell and Jess De Gouw, I’m fascinated about your relationships with them. Do you become, because of your relationship with Tony, both pillars of support for the actors? Does that continue on set?

Not really. I wasn’t on set very much. I was busy with Devil’s Playground when they were filming, which was shooting in Melbourne whilst I was in Sydney. So I met with them all and they were all great. I know writers are often really worried if performers change lines, I can live with that. An actor once called a line ‘wooden’ and I was quite upset, but he meant “I wooden say it like that” and he put it in his words and that was fine. Tony worked with the actors himself. He cast Alex, but he was too young, but by the time they got the film up two years later, he was perfect fro the role. Sullivan said we didn’t really need to change anything because it was all there. I think Alex has a tough role because he’s playing someone who’s got two things he wants to happen at the same time. I don't know if you would agree but the other characters are much clearer in their desires.

He has a massive transformation in the film, becoming the alpha male, which is interesting and I’m keen to see how it plays in the film. Especially since Alex and Sullivan are so physically different, that it must be quite a shift for the film.

What interested Tony I think was that he himself doesn’t have a background in crime movies or anything like that, his other films are focused on family dramas. He told me before filming that “You know the most aggressive thing I’ve directed was someone slapping someone” but I think that without giving it away, there’s a different kind of love story in the middle of this, and that’s what interested him and I in writing about it. Why hasn’t someone written this story before? Sullivan really breaks your heart in it which is interesting because he’s so violent and rageful.

Lucy Lawless as Alex Wisham in The Code

I’m curious in terms of that story two, there must be something in the water, where we’ve seen a lot of Australian dual protagonist crime films, such as Son of a Gun and The Rover. That they’re elemental films, which perhaps is a budgetary consideration, in trying to keep them contained, or do you think it’s something more thematically resonant throughout our culture?

I don’t know. The films that influenced me when I was writing this and I started a long time ago; I tried to write it as a novel; were things like Chopper and this Aussie two-part crime series called Blue Murder where the most engaging and interesting emotional relationships are between two guys. It’s not a romantic relationship but it almost is, because they offer the missing part to the protagonist. So I thought why does Australia tell that story so often. I don’t know if it’s necessarily budgetary, but when you see the film a lot of the supporting characters are kind of lost in the final edit it seems that the three way is the most interesting thing and we do stay with them much more. I think Tony and his editor Andy Canny, I think just every time they were on screen you wanted to be there and every time we went away it lost something; sometimes in scripts you put an architecture in of stuff to keep people interested and then realise you don’t need the stuff. If you’ve got people interested in the central relationships you don’t need the mafia poking in the window trying to get them for example. There’s a story about American Beauty where the shooting script was all set in a courtroom, so it’s the trial of the guy who does the shooting. They felt like we need that drama and Sam Mendes made the decision to just cut it all out and have the story. Obviously the right decision to make, but in the case of Cut Snake we had some more genre elements that we wanted in there because maybe I was concerned about the power of the central relationship, but it’s what makes the film interesting.

On the set of An Accidental Soldier

What was your involvement in the editing process? Were you editing Devil’s Playground and Cut Snake in similar locations?

I was all through the editing of Devil’s Playground which was amazing just to see the way how the different aspects of filmmaking were. So I had written ten or twenty hours of film and TV and never had been in an edit suite before. To realise, I was working with Martin Connor who was the editor of The Railway Man, just how an editor writes the film again and how they create meaning within the cut. It was amazing. That’s why I thought it was good for me to be in there because sometimes they’d make a decision to drop a line for performance and then you’d have to say “If we drop that, we’re gonna have to add some ADR in another scene, because that’s important”. Just to have that, to be there, given I’d read the script so many times was empowering. I didn’t get to see the editing on Cut Snake because it was done in Melbourne, so I saw a rough cut and gave notes on that. In a couple cases it was like they’d been in the edit room for so long that they didn’t see what I had seen. I have had the realisation that writing for TV is much more satisfying for writers than film. I think film really is a director’s medium. So I trusted Tony, he knew the script I wanted, I knew he was going to make his movie and I could help, but it would cease to be mine by that stage.

In exploring that particular delineation in your experience. If film is more a directors’ medium, and you’re working with directors who have completed features; and personally I’m of the perspective that I’m less concerned these days where the line between film and TV is so long as it’s compelling and good; but between Tony Krawitz and Rachel Ward, what was your relationship like between yourself as a writer and the directors?

I think it’s a question of the writer being able to play with the script for a lot longer in television. Directors are brought on later in the process. You get to write more, and tell a story over six hours, there’s a lot more words and a lot more writing and it feels like you can take smaller steps. There are some stories that are only ever going to work as film, but I’m starting to feel that for me anyway, the stories I want to tell, I want to take more time with and I want to explore different avenues. That’s what you do in a feature, you’re constantly pruning it back to the 90 or 100 minute experience, whereas in TV, the things I’m writing at the moment they’re 4-6 hours, that’s a lot of time to go off on tangents. So Rachel Ward was the set up director on Devil’s and Tony Krawitz came in to do the second half and they were extraordinary. Quite different people. Tony loves an argument, but he leaves the argument when it’s over, he’s not as sulky as me. He wants to get into it. Also Rachel’s not Catholic and Tony’s Jewish, I’m Catholic and in the show there was a lot of us catching up about details. Brothers and Priests aren’t the same thing for example. Just some really basic things, such as church hierarchy, what communion and confirmation is all about. For them you could tell it was like learning another language. Tony really jumped into it. They sort of come in at a later stage I suppose. With Cut Snake Tony Ayres was there pretty much from the second or third draft, so it became his story pretty soon. In the case of Devil’s Tony Krawitz is there three or four weeks before we shoot. So it becomes his version of our scripts. It’s much more collaborative I suppose, we write a version of the story and they film a version.

I’m curious on a side note, who won most of those arguments? Given your Catholic upbringing, did you have to be the guiding force in the detail oriented stuff? Was that something that was important to the overall show?

With the details, you know you’re making it for a broad audience, but one of the other producers is Penny Chapman who made Brides of Christ and she’s Catholic, along with Brian Walsh the commissioner at Foxtel. So with that stuff you just have to get it right. I would hate for someone even with a passing following of Catholicism to be distracted by that. Tony wanted to get into conversations about God and what these mens’ relationship to faith is, obviously because he’s working out how he’s going to be talking to the actors and that was a real treat, being on set and able to see within a couple of weeks how he and Rachel talk to actors. Not to be frightened of actors and directors input because they’re all trying to solve the same problems.

An Accidental Soldier

An Accidental Soldier

I’d like to talk a little about the writers’ room. It’s not quite the same here as it is elsewhere, particularly in the states because we hear more about it but how did that work on a show like The Code and how were you breaking story with the team? Dividing story and figuring out who’s gonna do what?

When I did Love My Way which was ten years ago that was the first show that used what they called the US model, which was quite exciting at the time because before then, you’d have a script department, which was frequently how people started, there’d be a head writer, script editors and some assistants. You’d make up the story of the week and then get a writer in, pitch the story to them and they’d go off and write it. That doesn’t happen in the states and it’s peculiar to Australia. What Love My Way did was all of the writers werethe script department. We met at Jaclyn Perces’s house and there was a whiteboard and we just came up with stories and then there was this sort of unseemly pause of like, “Who wants what?”. Of course there’s gonna be kick arse ones and there’s gonna be, you know, not as promising episodes. I was the total junior so I had to go, “No, you choose Tony McNamara” so we divvied it up, then we went away and all wrote scene breakdowns. In that case, there were three or four going on at the same time, so we’d read each others. Continuity wise I have had them end, here, you need to adjust that sort of thing, so there’s a bit of fluidity there. We’d go off and write our first drafts and that’s pretty much how every show is done now. So with The Code, Shelley’s was so complicated cause it was this political show and ends nowhere near you think. It’s quite a complicated conspiracy that unfolds. So we did the first four and it’s really a question of on the first day, you really broad stroke it, and then ask “where do we want to get to with this?”. Generally you’ll have a day or two on each episode, banging out points which will end up as a scene breakdown. You’ll go backwards and forwards with stories, which is what we did on Devils’ Playground, we realised that we pulled one whole story from an episode and put it in an earlier one, which is hard to do, but much easier at a document stage than if you’d realised when filming and you’d have to change things on the fly.

Just for my own interest, which came first? Devil’s Playground or The Code

They were both happening at the same time.

So how did you transition from being a show runner on one, to a writer on the other?

It was very hard. You asked before about do you think people will continue to adopt the show runner thing, so if you’re life’s not a showrunner, which is what I’m doing at the moment, it’s writing three shows at the same time. That’s just your life as a freelance writer, because they’re all at different stages of development and you only really get paid a living wage when a show goes, so you have to be on a couple to make sure one does go, cause frequently you’ll write a draft, it might not get up at the Screen Australia board meeting and it’ll be put on hold for a while. But it was so much better to just concentrate on one thing, I could give all my creative energy to just the one thing for a year and a half. It’s exciting to be on lots of different shows but I don’t think it’s really good for your writing.

When looking at the differences between the Australian and American approaches to writing a series why do you think there’s a seeming disconnect between certain audiences and shows, and whilst Australian drama does rate quite well, there are still certain US premium cable shows that rate higher?

I think it all comes down to time. Breaking Bad has eight full time people working on one episode for two weeks. They’re really going to explore the boundaries of that episode quite well. In Australia, the money around is that you get three people, for three days to do the eight episodes. If you’re really on song, and you’ve got really talented writers, with good underlying subject matter, I think you can capture lightning in a bottle. You can. But what you can’t do, is backtrack. You can’t afford to say “that was awesome yesterday but maybe we should just chuck it away and see if we can come up with something better”, which is what I’ve heard they always did on The Simpsons. The first days’ jokes they’d never use because they were the first things that popped into their heads, they had to think of the second things and they had the time to do it. Game of Thrones is interesting because obviously there’s this great appetite for fantasy, but Australia doesn’t make any of that. None. Kids a little but, but you cannot pitch sci-fi or fantasy in Australia. There’s a residual idea on networks that Australian people don’t won’t buy it if it has an Australian accent.

Ashley Zukerman as Jesse Banks in The Code

But even for dramas like House of Cards, and maybe I’m thinking of it wrong, and also that the commercial realities are changing, but if we’re able to spend more time on a show if that’s what’s needed to make it even better, in cases like The Slap where it gets remade abroad, wouldn’t that have a definite commercial benefit to the producers?

I don’t know. It does feel frequently like we need more time, but the great thing for Shelley Birse who created The Code; and it was a terrible thing too because she nearly went broke doing it; but taking the time to develop it meant that she could make the idea much better. But sometimes you’ll pitch a concept, especially for commercial networks and they’ve got a broadcast window, which might be nine months away so you’ve got to write, film and edit it in nine months and I just don’t know if you can do exceptional work. There was a feeling ten years or so ago where you were only judged by other Australian programs, but I think we’re now judged by American cable standards. If you have a choice and only one life to expend on watching drama then we have to make it better. It is frustrating and you do feel like you have to turn some things around faster than you’d want to.

It’s definitely not from a lack of talent I suppose. We have David Michod and Adam Arkapaw working on US shows, as well as Jane Campion with Top of the Lake. It’s wonderful that Devil’s Playgroundexists, it’s definitely a show on my wavelength. I do hope that with the introduction of services like StreamCo and possibly Netflix into Australia, that there will be an increase in the amount of drama that will be made. Do you think it’ll push the quality of drama higher?

Well look, if you think about it now, you can get Cate Shortland to write for you and Tony Krawitz to direct. That wasn’t the case a while ago, and when you have their names attached to a project, you can get good actors to read that script. When I started, the shortest series were 22 episodes. At that length, you can’t get Toni Collette to commit, but you can get her to commit to four. So on Devil’s Playground we could get her. Suddenly the cast know she’s in the show and everyone tries really hard. I’m not saying people don’t, but it’s suddenly as if everyone lifts their game. Since she’s in the show, it makes sense to Americans and I’m hoping more of those situations happen with shorter run shows, so we can get a higher profile cast involved which in turn gets a bigger budget. Though sometimes you just have to be lucky in what you choose to write about. We do get to see the best American shows, but when you’re over there you realise there’s 99 our of 100 stupid turkey shows that aren’t any good. Most of them are terrible ideas.

In terms of cinematography, I’m beginning to see less of a distinction between the cinematic language of film versus TV, given the improvements in cameras and big screens.

Andrew Commis was our cinematographer on Devil’s Playground and Simon Chapman shot Cut Snake, and I realised to call them cinematographers as well. I think I referred to them as DPs once and was quickly corrected. But now you’ve got people who are used to lensing stuff for film, so they don’t have as much time, which is hard for them, but it does look like a film. It makes you so much more excited about what you’ve made. Visual language makes up, it feels to me like 60% of the screen experience, so if you create that dark red, black, world of the church it does a lot of storytelling for you already.

I think that’s having such an impact on how both the audience and the filmmakers see the process. Too often shows will feel rushed, but nowadays, we’re getting closer to looking like films that there’s a real increase in the quality.

Well looking at the working relationship between Rachel and Andy, which is how we benefitted from the success of those Scandinavian dramas is that TV is all about close ups, mid-shot and then straight into the close up all the time. There’s very few close ups in the show. It’s shot like a film would be. That was a discussion with the broadcaster regarding that style because even that is a bit revolutionary for TV. Whilst TV is influencing film, film is definitely influencing TV. You don’t have to hit every close up all the time anymore which is very exciting.

Do you think that’s changed? How is it different from the past? Are networks increasingly lenient toward the show having a cinematic feel?

In the case of Devil’s Playground we had quite vigorous discussions and sometimes, I realised I was being a Home and Away hack, where sometimes I wanted to know why we weren’t seeing the face, but Rachel is very persuasive and she thought we’ve got a chance to do something really different. We can really announce this as a show that’s worthy to be on the same channel as True Detective. But you realise what prejudices you’ve absorbed on commercial TV until you start having a conversation about close ups and shots. We did have the big chats and then our investor NBC and Foxtel were very good in allowing us to do it. And if it worked, great, if not we’d talk. But we still had a lot of coverage so there were options, but by and large we trusted the filmmakers.

Finally, is there any advice you’d give to emerging writers and directors, particularly in light of the constantly evolving landscape of distribution and smaller run shows?

It’s something I think about quite a bit, because it is tough. What makes TV exciting now is also what makes it harder to break into. When you did have longer running shows, with a staff, there were more opportunities for people to get a start. To learn and make relationships with people who are going to have work subsequently and trust you. In addition to learning the work habits, if there is any advice I would give, producers respond just as much to a writer who hands something in on time, as they do if they’re the most shit hot writer. Sometimes it’s really good to do those simple things like returning phone calls and getting work in on time. That sounds incredibly boring, but there are some maverick producers there who’ll let you do what you want but that’s not the norm. What I have noticed is sometimes those creative friendships are really helpful as you all go forward in your careers and looking out for each other. There isn’t a career path any more. On Devil’s Playground one of the writers, Tommy Murphy, had a playwriting background, one was Cate Shortland and the other was Alice Addison who like myself who’d worked on various different shows. What’s exciting is that it feels like people are willing to take pitches from people in a way they weren't before. So if you have an idea, the bigger companies are vivacious in looking for new work. They might team you up with someone more experienced and if that’s the case I’d encourage you to not be defensive, because people brought it aren’t going to steal it, they want to help. But I understand that set of nerves around that. Finally, I think it’s important to write something for yourself. As opposed to all the other things you could do with your life, that might be satisfying, even when it happens for you and you’re being interviewed, like right now, no one gives a shit that I was in Toronto, compared to the actors, writing has to be about something you find surprising and energising for yourself than externally.